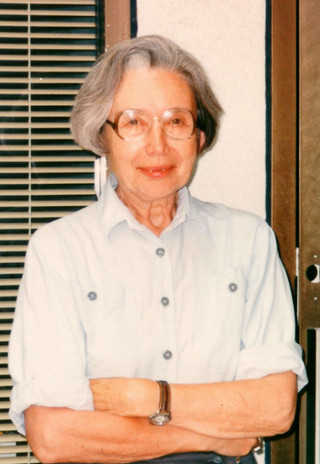

In Memoriam: Margaret Langdon

By Leanne Hinton, Amy Miller and Pamela Munro

October 31, 2005

Margaret Langdon, prominent linguist and professor emeritus of the Linguistics Department at UCSD, died on October 25, 2005, in Bishop, California, where she had moved recently to be with her daughter. Professor Langdon was the primary expert on the linguistics of Diegueño, now often referred to as Kumeyaay -- an indigenous language (or set of very closely related languages) of San Diego County.

Margaret Langdon (nee Storms) was born in Belgium, and spent her childhood there, her teen years marred by the traumas of World War II. Anxious to put bad memories behind her, she emigrated to the United States after the War, her first job in this country being for the Belgian airline Sabena. Eventually, she became a student in the Linguistics Department at the University of California at Berkeley, receiving her Ph.D. in 1966. As a graduate student, she came to San Diego to do fieldwork on Northern Diegueño. She worked closely with two fluent speakers of Northern Diegueño (also known as ’Iipay Aa), Ted Couro and Christina Hutcheson. Through her work with them, she created the first substantive grammatical description of the language for her dissertation.

During this time, she also met her husband-to-be, Richard (“Dick”) Langdon, who owned a piece of property in San Diego where he developed a large orchard of lychees and other exotic fruits. Dick, a lanky six-footer, was raised along with several even taller siblings by their 4’ 10” Chinese mother, who had been brought to the United States by her American husband. He had left the family when Dick and his brothers and sisters were small, and their diminutive but tough mother, who barely spoke English, raised them by herself in San Diego. Dick was a roamer of the backroads of San Diego and Baja California, and had many Kumeyaay friends himself. For the adventurous Margaret, there was no better match.

Luckily, this was the time when UCSD was just starting to develop as a full-fledged campus of the university system, and Leonard Newmark, the founding chair of the department of Linguistics at the young campus, offered her a position there. With her husband, her home (built by Dick), a child soon to come, her language of study and a job she was to excel at all in San Diego, Margaret Langdon was there to stay.

Langdon remained in the Linguistics Department at UCSD until her 1991 retirement, chairing it from 1985 to 1988. Langdon and her family also maintained close relations with the Kumeyaay communities, visiting and being visited often, and attending peon games and other tribal functions, often bringing students along. For Margaret, the Kumeyaay way of life became part of her own way of life. After Dick died in 2000, Margaret and their daughter Loni held a memorial ceremony for him a year later in the traditional Kumeyaay manner, which involves a feast and performances by bird singers. Life at the Langdons’ was filled with diversity. Parties at their house were generally attended by a combination of professors and students, plumbers (Dick’s profession) and tree growers, Kumeyaay singers and peon players, and friends and relatives of all kinds.

At a time when many of her colleagues were interested only in what a given language could reveal about linguistic theory, Langdon was concerned with language as a complex and internally coherent system. This concern is evident in her descriptive work on Mesa Grande, notably A Grammar of Diegueño: the Mesa Grande Dialect, the Dictionary of Mesa Grande Diegueño (which she published under the names of language consultants Ted Couro and Christina Hutcheson, in 1973), and several additional texts.

Throughout her career Langdon recognized linguistic diversity in the Diegueño area. She addressed the topic explicitly in several papers and implicitly through her involvement in numerous tribal dictionary projects and language programs, concluding in 1991 that at least three distinct languages could be recognized within the Diegueño dialect continuum.

Originally trained as an Indo-Europeanist, Langdon was also fascinated by the prehistory of Diegueño and the other Yuman languages, and the larger, still controversial Hokan stock of languages with which they are connected. She wrote many papers on the comparative or historical morphology and phonology of these languages. She also received a large grant from the National Science Foundation to compile extensive vocabularies and lexicons of Yuman, making a relatively early use of large-scale computational comparison.

Langdon was keenly aware of language as a vital part of the heritage of its speakers, and devoted much of her career to working with Native American communities to preserving this heritage. Children stopped learning Diegueño several generations ago, one instance of a world-wide decline in indigenous languages as the global economy and world languages overrun them. Yet the descendents of the last speakers are making efforts nowadays to learn their ancestral tongues, even if they can only learn them as second languages. Professor Langdon was a pioneer in what is now a growing field of “linguistics for the community” -- in her case, developing publications and materials for second-language learning by Kumeyaays. Among the first of its kind was the book of language lessons called Let’s Talk ’Iipay Aa: an introduction to the Mesa Grande Diegueño Language (1975), co-authored with Couro. This user-friendly book, along with the Dictionary cited above, is still used today (in photocopied form, since it is out of print) in Kumeyaay language classes. In order to write these books, Langdon devised a practical orthography, again one of the earliest of its kind, that could be easily typed without special symbols. This writing system is immortalized in such venues as the name Kumeyaay Highway, on Highway 8. Let’s Talk ’Iipay Aa, was a collaboration with an eager set of graduate students, a book full of excellent grammar lessons, which, when mastered along with the vocabulary from the dictionary, would allow learners to develop impressive conversational proficiency. It is a labor of love, with idioms, stories, songs and illustrations blended in with the lessons. More recently the Barona tribe worked with her to produce a new dictionary for their own community, published by the tribe. Langdon had begun work on a revised and expanded edition when illness overtook her; one of her former students has now taken over the project.

She was also the founder of a long-lived annual workshop on Yuman languages, and their distant relatives within the Hokan stock. Later the Hokanists were also joined by linguists working on Penutian, another stock based partly in California. Through this annual meeting, a strong core of linguists from many places and backgrounds found camaraderie and intellectual partnership. The workshops produced working paper proceedings that were often the first publications of graduate students, and which hold in them an enormous amount of information on Yuman and other Hokan languages. As a service to everyone studying Yuman languages, she also kept a running bibliography of publications, which she passed out at the workshops, and eventually published. The same year, she worked with other scholars to produce other useful bibliographies, on Hokan, Chontal, and Jicaque .

Langdon also developed an archive of Yuman languages in the Linguistics Department at UCSD, affectionately known as the “Yuman Room,” which included all publications on Yuman languages and large collections of unpublished fieldnotes of many linguists. Before moving to Bishop, she made arrangements for the unpublished materials in the Yuman Room to be housed in the Bancroft Library at Berkeley.

Langdon was a talented and generous mentor to her students, as well as students from elsewhere who crossed her doorstep. Her door was always open to them, and she never gave the impression that she needed to be doing something else other than talking to them. Her students were welcome in her home, and she and her husband and daughter maintained lifelong friendships with them. It was through her leadership that the Yuman languages became one of the best-studied language families in California, with students doing dissertations and other research on the various languages in that family under Margaret’s tutelage, and later the tutelage of her own students turned professors. Langdon’s students have become professors in most of the major universities in the west.

Langdon is survived by her daughter, Loni Langdon, who lives in Bishop, California, a sister in Belgium, and her many students and colleagues who held her beloved.

Langdon Memorial and Media Project

In the field of language preservation, the career of Dr Margaret Langdon, professor at UCSD from 1965 to 1991, stands our for its extraordinary breadth and impact. Langdon, who passed away in October 2005, is best known for her invaluable contribution to the study of several Native American languages of the west coast, of which her work in Kumeyaay is perhaps best known.

A large donation of Dr. Langdon’s collection of books is currently available in what has been unofficially named “The Langdon Collection of Native American Literature”. With the support of a donation to the university from Abe Halpern, for the advancement of Native American Studies, the collection has been augmented with reference materials. The funds also supported the acquisition of new equipment for digitizing analog recordings, and a goal of the project is to preserve the work amassed both by Dr. Langdon and by other linguists, ensuring access for generations to come.